Subscribe To Our Newsletter

Subscribe to our newsletter for new product updates, and exclusive discounts

Indestructible. The goal was to build the most indestructible logger shoe in the world. Timber in the Pacific Northwest was gold in the 1920s. It peaked at 39 billion board feet in 1926. The industry was booming. From Maine to Washington, handfuls of boot manufacturers, big and small, competed for the cold hard cash loggers were pocketing, but only one of those boots still survives today: the ‘White Logger.’ The rest are dead and buried in museums and libraries.

In 1880 — more than 50 years before the White Logger was outcompeting more expensive boots from Curren, Bergmann, and Forester — J.P. White pioneered a handsewn boot for loggers in Virginia. By 1916, it had been perfected by his son, Otto White. It looked different, it felt different, and history would prove that it possessed the dominant traits and characteristics that are best suited to survive in unstable environments—industrial, economic, and technological. It was fitter and stronger than any other boot.

Fallers, buckers, choke setters, drivers, and climbers in the Pacific Northwest were faced with unrelenting terrain that mimicked the Hindenburg Line. Washington, Oregon, Idaho, and Montana were a Western Front of their own kind. Mountainous regions and volatile weather patterns proved difficult for logging outfits who looked to plunder the wildlands. Filson, Pendleton, and Woolrich rushed to put their textiles to the test while more than 30 boot manufacturers offered to hob and calk their boots for loggers.

While most of the boot manufacturers faltered during the Great Depression—cutting their stock levels or closing up their shops—Otto White began to stock more logging boots in his Spokane shop than any other company in the country. He hired more bootmakers, built more boots, and absorbed the business of weaker specimens one by one. Like timber production, which fell from 39 billion board feet in 1926 to 10 billion in 1932, the demand for logging boots was in decline, but not for the White Logger. Its reputation was bolstered by the loggers who wore them, word of mouth, and by a few hand-selected dealers in Oregon, Idaho, and Montana.

The strength of the White Logger began to spread but it was about more than just survival. Not only was it thriving in a time of economic crises — costing more than a week’s worth of pay — but it was the catalyst for Otto White to introduce more boot styles in the 1930s than any other American boot company in the country. The Lineman, Sportsman, Packer, Semi Dress, and Oxford were designed and built for a mass of American workers who needed more than what the market was offering. If a man ‘worked and walked’ it was best to buy a pair from White’s Shoe Shop in Spokane.

To thrive in the Great Depression, it takes more than just one dominant trait. For the White Logger, three distinct traits endure to this day, and their prevalence can be found in every branch of the bootmaking tree in the Pacific Northwest, from Nick’s, J.K., Frank’s, and Cruz Boots. The influence of the White Logger is indisputable, but why?

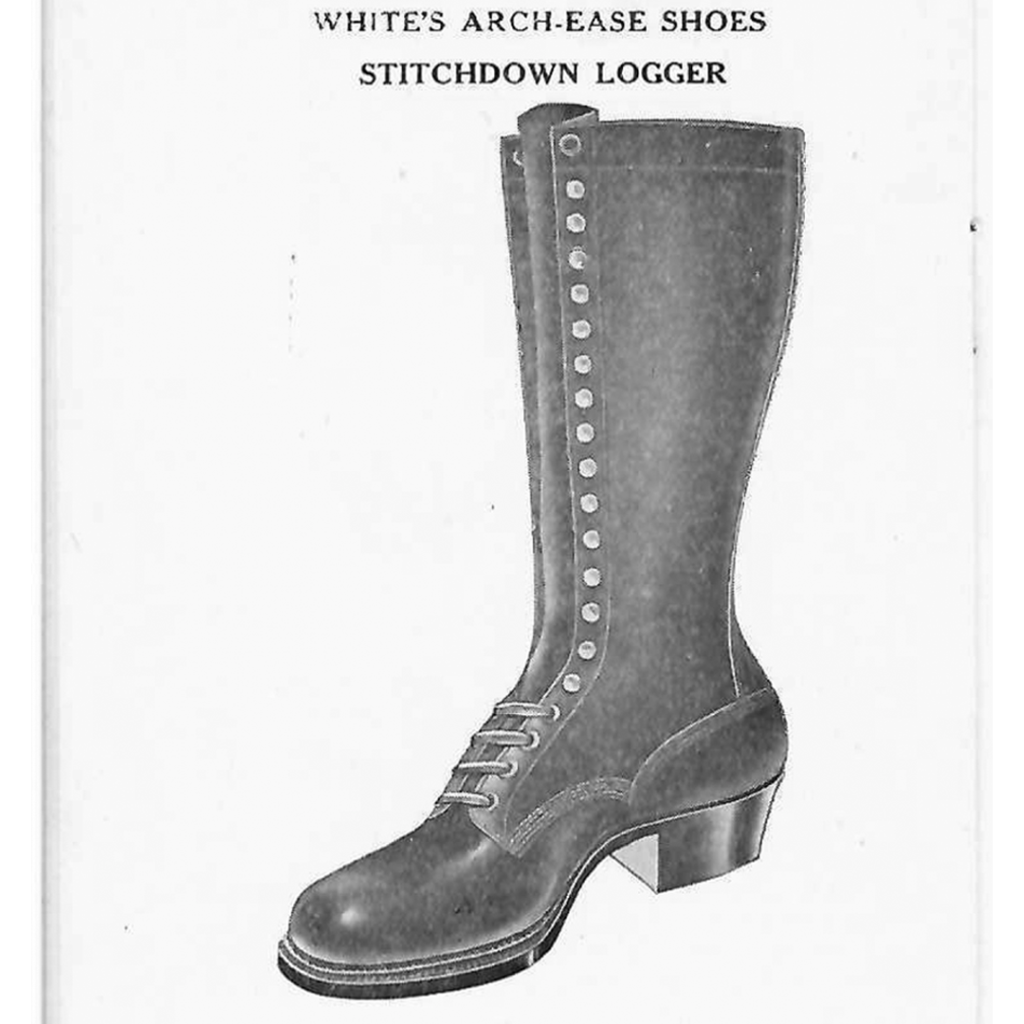

The Genuine Stitchdown Logger

“There was never a shoe built like this until we built it.” -Otto White, 1930

Otto White built varying styles of naildown and stitchdown loggers, but nothing will surpass the height of strength and comfort produced in his genuine handsewn, rolled-welt White Logger. It was pitted against every logging boot in the country. They all died out. It’s the same boot that loggers asked White’s bootmakers to rebuild so they could wear them for decades even when they mistakenly cut through the uppers with a chainsaw and filled them with blood—all true stories. An original handsewn logger — not a machine stitchdown — is a rare breed. It’s still the king of the Inland Empire and White’s bootmakers still sew it the same way Otto did.

The Logger Arch

“You can get Arch Support if you put your feet in a vice.” -Otto White, 1930

Nothing embodies the innovation of Otto White more than the original Logger Arch. It made the boot feel better than any other boot. If there is one dominant trait of the White Logger, it’s the high, strong arch of the footbed. All 26 bones of the foot were studied, the resting shape of the foot, and the arches and heels were calculated by increments to perfect the position of the heel and toes against the earth. In 1926, at the height of timber production in the U.S., the Arch-Ease trademark was registered. Otto would never publish another catalog or ad or order form without brandishing the Arch-Ease logo.

The Logger Heel

“Soft and pliable and wears like iron.”

Logger heels and work boot heels in the 1920s were short, stout, and usually blocked. On occasion, some manufacturers sanded a slight curve into the stacked heel, but without a high arch, there was little room to set the heel toward the strength of the arch and build a foundation at the bottom for it to rest. Otto was the first to raise the height and sand it from a block to an angular, practipedic shape. There is no Logger Heel without the Logger Arch and Otto White was the forerunner for both. He perfected it.

All of the small things started to add up: the handsewn rolled-welt, the high Logger Arch, the practipedic Logger Heel, including two patents in 1916 and 1927. The first patent was an invention called the O. White nail, a tempered steel twin nail. It saved 1 ¾ pounds of leather in each pair of boots. It led Otto to claim that his logger was more comfortable, with lighter weight, and longer service. He was right. Otto would improve on the patent in 1927 when he invented a twin calk with removable and replaceable points or spurs, produced by Spokane Tool and Die. Otto’s dominance through the industry decline of the 1930s was not left in the hands of fate. It was found on the feet of every logger and driver and cruiser who could afford to empty their pockets.

Stories of the White Logger are endless. It’s been called many things—the Smokejumper, the Cruiser, the Sportsman—and all the other names Pacific Northwest bootmakers call it, but there’s only one genuine White Logger. It’s the only handsewn boot to survive WW1, the Great Depression, WW2, and every other war and recession in the history of the 20th century. More than 30 boot manufacturers sold loggers in the 1920s and 1930s, but none of them are left to tell their story. They’re all extinct. Not just the strong but only the strongest survived and will still survive in the Pacific Northwest. The trunk — and all the branches of the tree — will survive.

Jacob Mannan, Archivist